Can There Be a Masterpiece Without God?

Short Answer: No.

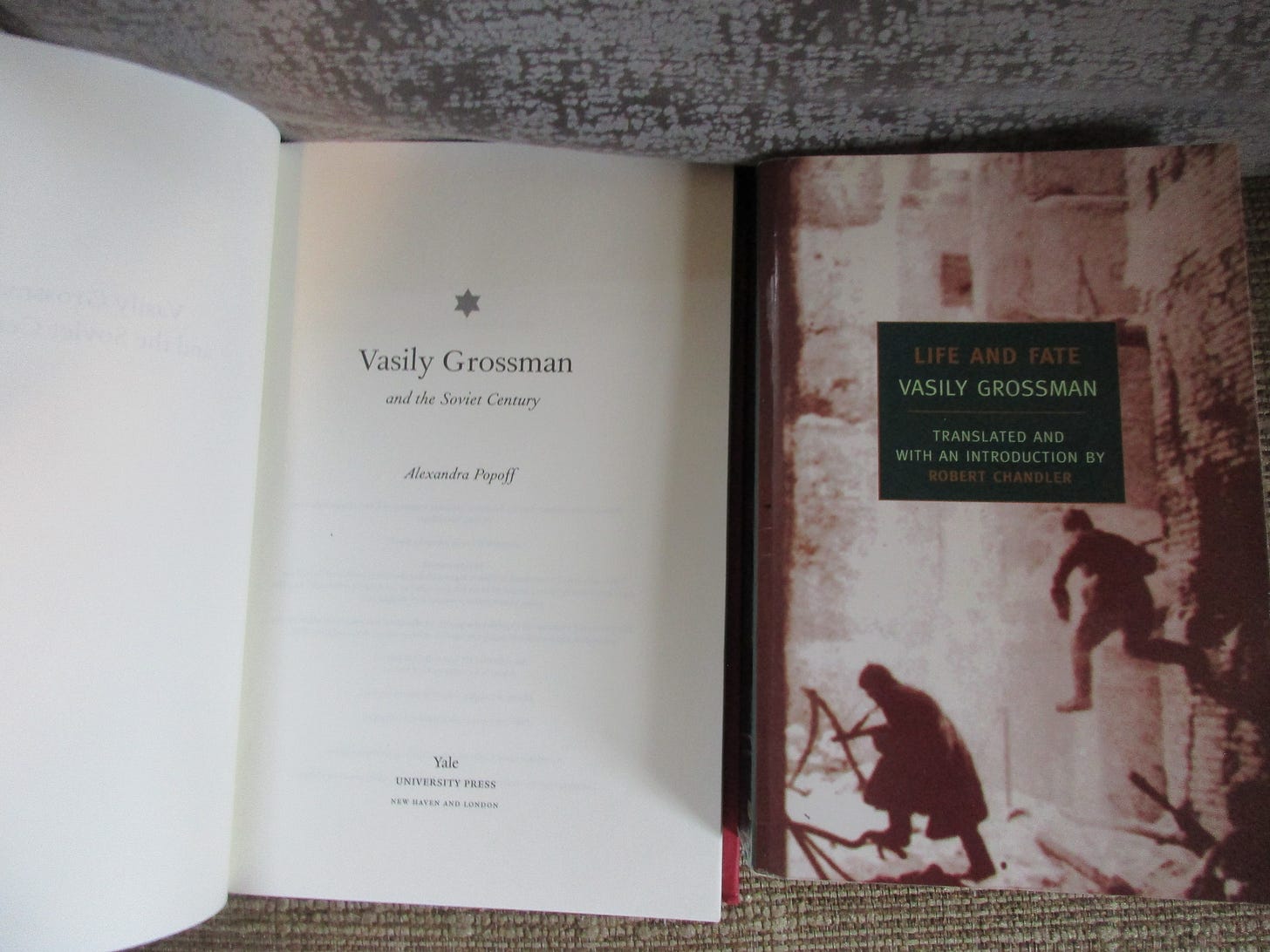

How does one survive the brutality and deprivation of war? How can human bonds remain intact under totalitarianism? Why do men give in so readily to power, and do women handle affliction differently than men? Vassily Grossman answers these questions up to a point in his massive novel Life and Fate. Grossman, a noted war correspondent, concluded that “freedom” is the thing to be desired, but what does he mean by that word? Lack of coercion. Speaking without fear. Having material needs met. But all this has little room for a recognizable God.

When Tolstoy wrote War & Peace he still retained some measure of Russian Orthodox faith; that fact shows in the sweep of the novel and its flashes of providence and divine intervention, as well as the faith of individual characters. Grossman, born into a Jewish family in Ukraine, has no such treasure trove with which to enrich his novel of WWII. Dostoevsky’s novels have startling power in large part because of characters rejecting God, which leads to shocking behavior. Grossman’s characters are normal humans, and hence riddled by original sin. Their transgressions are to their minds crossing the lines of some ill-defined morality: adultery, theft, lying, etc. The only fear is of the state with its monolithic power to praise or damn, but especially to re-define.

And so, Life and Fate is not a masterpiece, but it is one of the most effective treatments of totalitarian power in print, on par with The Gulag Archipelago and in some ways more conducive to reading because it does follow a number of characters. The central event is the battle and siege of Stalingrad, of which Grossman is a master chronicler. As he describes the titanic struggle, it is the crux of the whole war, and he makes a strong case for that view. But the novel (all 871 pages in the NYRB edition) presents problems to the reader: is there much to choose from between the Nazis and the Soviets? How can one root for one of those totalitarian powers but not the other, seeing that in their crushing of the human spirit and denying God they both fall prey to human folly? Grossman shows that Soviet anti-Semitism, while hardly as murderous as the Nazi “Final Solution,” is in many ways just as insidious. He does not spare all the other Soviet attacks on its purported enemies, such as the 1937 purges and show trials, from being seen in their ghastly effects. What is most disturbing is how the state’s power corrodes ordinary life: work, habitation, love, conversation. Families are ripped asunder and divorce is commonplace. Ideology is supreme, even during a war when the state is under threat—men on the front lines are arrested and interrogated for apparently no reason.

In this dystopia kindness is depicted. But is kindness enough? Some kindness is better than none, but it is hardly enough upon which to build a civilization. Kindness cannot defeat the brutality and evil of the gas chamber, the concentration camp, or the torture rooms. Only Christ can do that, and Christ is absent from these pages.

Naziism was defeated and largely undone after the war; Communism stood for another forty years…as a state power. Then (except for China, Cuba, and North Korea), it went underground, where it has been eating away at the world for another forty years. As I understand it, Pope John XXIII dearly wanted Orthodox representation at Vatican II. Negotiations with the Soviet-controlled Russian Orthodox Church got him observers, but at the cost of no denunciation of Communism. That surely has to rank as one of the worst and most one-sided deals in history.

Grossman criticized the Soviet state and paid a heavy price. But what he proposed in the pages of Life and Fate, as skillfully as it is artistically constructed, is not really a solution to the problem of state power.

Recommended Reading: Anything by George Orwell, The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, and Darkness at Noon by Arthur Koestler.

Alexandra Popoff’s Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century is an insightful and informative biography of Grossman.