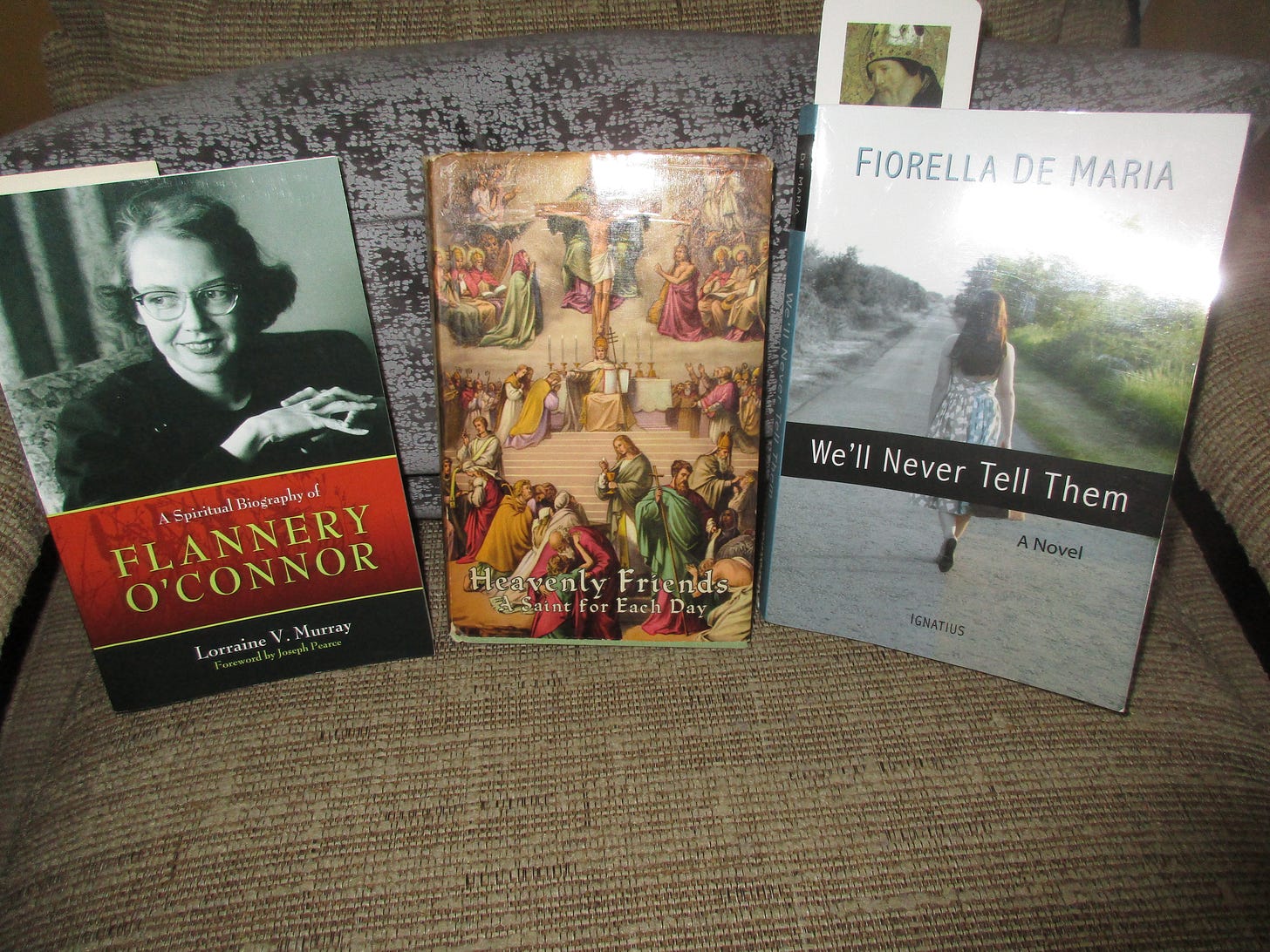

Some recent reading. Blessed Feast of All Saints, our friends and family in God’s company.

Second Excavation: 1895 and 1899, The Carrot and the Stick

Sheen wrote: “Our Declaration of Independence affirms that this country believes in God. Americans should take this literally.”32 Does America believe in God? Do Americans? If so, what does that belief look like? Is it a Catholic set of beliefs? Or are there problematic elements in the faith of America? Pope Leo XIII has some thoughts on the matter.

In 1895 the Holy Father Leo issued his encyclical on Catholicism in America, Longinqua. That was an encouraging missive to Catholic America. But four years later, the same Pope came out with his apostolic letter Testem Benevolentiae, Concerning New Opinions, Virtue, Nature and Grace, With Regard to Americanism. This second message to America decried some heterodox beliefs here in the New World.

First the carrot. The Holy Father sings America’s praises in Longinqua’s opening paragraph. “We highly esteem and love exceedingly the young and vigorous American nation, in which We plainly discern latent forces for the advancement alike of civilization and of Christianity.” In paragraph two Leo brings up the 1892 Quatercentenary celebration of Columbus, the Catholic explorer. It was a moment of recognition of the Italian diaspora in America.33 (Although the elapsing of another century would see an erosion of that recognition.) The Pope then quickly spins through a history of Catholicism and its American achievements, especially the evangelization of the First Nations. But he also notes the establishment of the U.S. with the help of Catholic France. Subsequently, an American hierarchy was established.

He then argues that (the true) religion is an aid to public morality. Pope Leo lauds the U.S. for not hindering religion, but does not make an unqualified endorsement of the church-state separation. “[I]t would be very erroneous to draw the conclusion that in America is to be sought the type of the most desirable status of the Church, or that it would be universally lawful or expedient for State and Church to be, as in America, dissevered and divorced.” Indeed he asserts that if the Church would be even more successful if “she enjoyed the favor of the laws and the patronage of the public authority.”

The Pope continues his message by discussing the growth of Catholic education at all levels in the U.S. but especially at the university level. The growing power of the United States and the maturing of its Catholic hierarchy and institutions has, Leo XIII reminds his readers, been recognized by the Holy See by “the due establishment…of an American legation.” That establishment implies the supremacy of Rome as a check on any possible independent tendencies in American Catholic minds and hearts. “But how unjust and baseless would be the suspicion, should it anywhere exist, that the powers conferred on the legate are an obstacle to the authority of the bishops!” In other words: Rome is the final authority, but the American bishops need to do their job of shepherding in America. “All intelligent men are agreed, and We Ourselves have with pleasure intimated it above, that America seems destined for greater things.” One hindrance to positive growth was divorce, and Pope Leo forcefully upholds the magisterial teaching as good for families and the nation.

Next, the Pope noted for his attention to the condition of the workers warns American workers and those empowered to guide them against joining societies or unions that might lead them to deviate from Catholic teaching. He tries to rally Catholic journalists and writers to focus on promoting Catholic causes, especially due to the fact of America’s religious diversity.34 Speaking of religious diversity, Leo XIII does not shy away from calling American Catholics to lovingly evangelize the surrounding non-Catholic population and culture. “Surely we ought not to desert them nor leave them to their fancies; but with mildness and charity draw them to us, using every means of persuasion to induce them to examine closely every part of the Catholic doctrine, and to free themselves from preconceived notions.” He makes special mention of “the Indians and the Negroes” of America, “the greatest portion of whom have not yet dispelled the darkness of superstition.” All-in-all Longinqua strikes a tone of encouragement and approval, albeit with reminders to the revolution-spawned republic of Papal supremacy.

Then the Leonine stick of 1899.35 Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae (Concerning New Opinions, Virtue, Nature and Grace, With Regard to Americanism)36 is a stern warning to the independent-minded amongst American Catholics that they are not free to improvise on magisterial teaching. As Peter Kwasniewski puts it, in “Leo XIII’s letter, the basic problem of the Americanists is a naïve reconciliation with modernity that takes the form of accommodation to a prevailing Zeitgeist rather than a confrontation and conversion of culture.”37 While much of Leo’s salvo is aimed at the ideas of the decidedly non-traditional Father Isaac Hecker (1819-1888) and his followers,38 Testem Benevolentiae can also be seen as an assertion of tradition and practice as mediated by Rome. I turn again for further elaboration to Kwasniewski who describes the Americanist emphasis as a sort of forerunner of the widespread delight in change and alteration that accompanied Vatican II, as well as the tendency to eschew deep thought in materialist America. “For its part, the Americanist exaltation of activity, of keeping busy and productive, anticipates and informs a number of catastrophic liturgical principles, such as the superficial notion of ‘active participation’ that gained ascendancy during the revision of liturgical texts and the consequent rejection of contemplative, serene, subtle, and poetic elements, anything that savored of long maturation, profound meaning, and effort-asking asceticism, all written off as relics of the monastic and medieval past.”39 Separated from their European roots, land, and culture, Americans are not prone to think of themselves in any sort of continuity with the glories of the Middle Ages.40

Leo began the 1899 letter with a brief reminder of his regard for America and its promise, but quickly turns to admonition over errors. The Holy Father refutes false opinions of the necessity of watering down the faith. “Many think that these concessions should be made not only in regard to ways of living, but even in regard to doctrines which belong to the deposit of the faith.” Leo dispels this false idea by referring to the decisions of the First Vatican Council held under his predecessor, Pius IX. “For the doctrine of faith which God has revealed has not been proposed, like a philosophical invention to be perfected by human ingenuity, but has been delivered as a divine deposit to the Spouse of Christ to be faithfully kept and infallibly declared. Hence that meaning of the sacred dogmas is perpetually to be retained which our Holy Mother, the Church, has once declared, nor is that meaning ever to be departed from under the pretense or pretext of a deeper comprehension of them.” More than that, Leo inveighs against an independent mindset concerning Catholic belief. “But, beloved son,” he writes Cardinal Gibbons, “in this present matter of which we are speaking, there is even a greater danger and a more manifest opposition to Catholic doctrine and discipline in that opinion of the lovers of novelty, according to which they hold such liberty should be allowed in the Church, that her supervision and watchfulness being in some sense lessened, allowance be granted the faithful, each one to follow out more freely the leading of his own mind and the trend of his own proper activity. They are of opinion that such liberty has its counterpart in the newly given civil freedom which is now the right and the foundation of almost every secular state.” America, of course, being a prime example of the secular state.

Leo further warns about the danger of “confounding license with liberty” and trying to live out the Christian life solely by reliance on the natural virtues and no recourse to the Holy Spirit. Near the end of his missive, the Holy Father sketches out two mutually exclusive paths for Catholic America. “From the foregoing it is manifest, beloved son, that we are not able to give approval to those views which, in their collective sense, are called by some ‘Americanism.’ But if by this name are to be understood certain endowments of mind which belong to the American people, just as other characteristics belong to various other nations, and if, moreover, by it is designated your political condition and the laws and customs by which you are governed, there is no reason to take exception to the name. But if this is to be so understood that the doctrines which have been adverted to above are not only indicated, but exalted, there can be no manner of doubt that our venerable brethren, the bishops of America, would be the first to repudiate and condemn it as being most injurious to themselves and to their country. For it would give rise to the suspicion that there are among you some who conceive and would have the Church in America to be different from what it is in the rest of the world.”

That is a prophetic warning from a loving father. Surely today’s status quo with its loss of a common language, endlessly variable liturgy, and hodgepodge of orthodoxy and heterodoxy is a manifest validation of the truthfulness of Pope Leo XIII’s warning. His successor took up the battle on a grand scale in the next century.

Notes for this section:

32. Sheen, Dependence, 34.

33. One well-known example is St. Frances Xavier “Mother” Cabrini, but another fascinating story is that of Sister Blandina Segale (1850-1941) of the Cincinnati Sisters of Charity. She served twenty-two eventful years in Colorado and New Mexico. Her At the End of the Santa Fe Trail (Arcadia Press, 2019) shows the possibilities of active but prayerful ministry by orthodox habited religious as opposed to many political pant-suited post-Vatican II nuns. Sister Blandina’s time in Santa Fe overlapped with Archbishop Lamy’s (of Willa Cather’s lovely Death Comes For the Archbishop fame) tenure—she spoke very highly of His Excellency.

34. I confess to wishing for a Leo XIII moment of reckoning and truth for today’s heretical National Catholic Reporter, the epitome of a disordered and disobedient American “Catholic” press.

35. For context we should remember that in four years the United States had taken on the trappings of empire by going to war with Catholic Spain and gaining control over large Catholic populations in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

36. Latin text at https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/la/letters/documents/hf_l-xiii_let_18990122_testem-benevolentiae.html (Accessed June 22, 2023); English translation: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/leo13/l13teste.htm (Accessed June 22, 2023).

37. Peter Kwasniewski, Resurgent In the Midst of Crisis, (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2014). Chapter Four of that fine book (“Contemplation of Unchanging Truth,” pp. 57-70) is concerned with the Americanist heresy and liturgy. For a different perspective, see Patey, op cit. 281-282).

38. For Hecker see https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07186a.htm; for the greater controversy over “Americanism” see https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14537a.htm (Both URLs accessed June 22, 2023).

39. Kwasniewski, Resurgent, 60.

There are, of course, exceptions. Henry Adams made his mark in Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres; Mark Twain with A Connecticut Yankee and Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc; and architectural collections such as The Cloisters. Nonetheless, I would argue that Americans do not see themselves as heirs to the Medieval period because crossing the ocean and settling in the New World closed that door.